Northern Kenya: The edge of the Ndoto Mountains

I have never heard such a musical language. To me, a listener and crudely amateur speaker, the Samburu language seems comprised of a smattering of letters and indistinct phrases, but mostly, it is song. I am sitting on my porch and the meeting of four Samburu “Wazees” (old men) blown my way on the warm wind. They are praying. Together. Just like yesterday. And just like yesterday, I will fall asleep to the rocking lullaby of people talking, singing, laughing.

To respond to the greeting ‘Supa’ is ‘Oh Yea’, which sounds simple enough. Yet the transference of this message relies wholly upon the tone, tempo and lilt in my voice, all this while my tongue and mind work in frenzied unison to ensure correct meaning and double-check cultural and situational appropriateness. God help me if they actually respond. The language is heavily comprised of vowels, which are responsible for the soft sound, but is eternally tricky for the outsider. In English, we rely on our consonants to deliver the sharper quality, and meaning is less dependent on whether we hit the right musical note on our response to ‘How’s it going, mate?’

As a language written more by melody than letter, foreign speakers are remarkable inept. Laura, my American friend, has been working, living and raising her two proficiently multi-lingual children here for the past 19 years – yet, her children laugh at her spoken Samburu, and her son Loiweti tells me that the Samburu language never sounds the same coming from a foreigner’s mouth.

To my un-tuned ear, both parties repeat the main greeting, ‘Esearian’ a number of times. They don’t rush into the conversation. People here have time. The goats, cattle and camels are brought out to the wilds after chai and sun-up , and brought in as the sun touches the western peaks of the Ndoto’s. The space between is filled with conversation, song, naps and steps taken with long strides and an easy gait.

A Kenyan friend of mine works at an international computer company that has an office in Nairobi. He tells me about how his Western bosses organise meetings with the locals and charge in, hitting the ground running, telling the locals what they need and require from the moment they open the conference. This, my Kenyan friend tells me, is not how meetings in Kenya work, nor is it how most Kenyans work. He tells me that first a meeting should be called where they drink tea and chat about families, weather, farming… anything but the topic. Then a second meeting will take place where the manager might, very casually, give an overview of the company and what his section does within it. Finally, a third meeting will take place, where the manager will tell the guests what he is asking of them. This process takes weeks. This process takes relationship.

People here have time.

The Ndoto Mountains

The words ‘boredom’ and ‘stress’ do not have existing counterparts in the Samburu language. Laura’s husband is a Samburu and amidst the steady flow of Samburu chatter that floods the air when he talks with friends, the word ‘stress’ is spoken in English. It seems it was never a word that was required prior to English unfurling its way into Northern Kenya, a word of which there is no native equivalent.

Mobile phones are changing this though, and ‘time is money’ and ‘pay per minute’ frustrate those wishing to ask a quick question of a friend, but are bombarded with ten minutes of inquiry as to one’s health, the wellbeing of their livestock, weather and children, and then the health, livestock, children and weather where one’s mother, cousins, brothers and sisters reside.

People here have time.

Even I, armed and fully loaded with my western baggage of ‘missing out’, ‘be productive’, ‘work harder’ and the inevitable guilt when doing nothing, am lulled by the heat and the songs of the livestock, birds and humans enough to sleep in my circular hut after lunch, and sit for hours on my porch to watch, to read and to write. My evening strolls up the sandy river seep in through my bare feet and words and inspiration slip and slow-dance into my mind. Unarmed and unsuspicious, I am given positive thoughts about my future, joyful and relaxed with a genuine sense of gently looking forward, rather than the frenzied, anxious ‘planning’ I have become used to. And it is good.

However, with the invention of the word ‘boredom’ and the introduction of alcohol, communities and families are plagued by alcoholism, alcohol-fuelled violence and promiscuity. Traditionally nomadic pastoralists, hundreds of years of a certain lifestyle have been put to an abrupt halt with the settlement of families in one place, for life. Schools, churches and medical dispensaries have lured families, and land degradation, depleting water sources and lack of waste disposal infrastructure and, (dare I say) boredom has resulted.

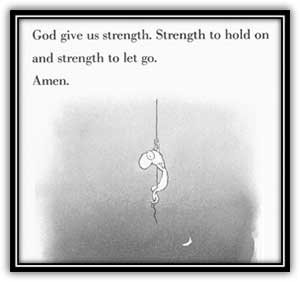

It seems far north Kenya is struck by the same condition as the rest of the world and the hearts of those within it. The struggle between holding on to what is worthy and enriching, whilst moving and growing and stepping forwards. The ‘figuring out’ of what is good and what is not. The apathy and laziness before the concern and experiments and awakenings inside us all.

By Michael Leunig

Still, for the moment I breathe in the smell of smoky camel milk and scented wood from the fire. I walk barefoot over last night’s elephant footprints in the dry river beds. I listen to the constant day time symphony of wooden camel bells and wazees outside my hut, voices and sounds so many and so light it is as though I am listening to a bubbling river.

I have time. And it is good.

*This writing is old! Just over two years old – as I was in Kenya last in early 2014.

Very appropriate cultural comments, especially about planning the future (favorite western remark ‘what are your plans’?)and the creeping concept of boredom. Looks and sounds a great place to settle down and relax. Pity about the introduction of alcohol, mobile phones and increasing sedantarisation (correct word or not?)